The statistics around bird strikes and airports are enough to leave you reeling. The sheer scale of the problem and magnitude of its occurrence is one of modern life’s lesser-known by-products. And it’s on the increase due to the amount of flights we, as humans, are taking.

With more flights operated by a greater choice of airlines that use an ever-increasing number of airports, the effect on birdlife is staggering. We’ll review those mind-blowing figures and stats in a moment before we hone in on the available courses of action to ensure bird strike prevention at airports.

Airport bird strikes by numbers

Bird strike – collision with windshield of plane

- The vast majority of incidents where a bird collides with a plane happen during take-off or landing (Source)

- There are more than 13,000 bird strikes annually in the US alone (Source)

- However, these cause just one human fatality a year…

… and an average of only 12 injuries (Source) - Most incidents of bird strike (65%) cause only minimal damage to the airplane(Source)

- But, particularly if the collision is with the plane’s windscreen or if the bird is sucked into the aircraft’s engine, the resultant damage can be costly(Source)

- The annual cost of bird strikes to worldwide commercial planes is estimated to be $1.2 billion each year

(Source) - The annual cost to the decline of many avian species is harder to calculate but is of increasing concern (Source)

- According to the Federal Aviation Authority, incidents of bird strikes are growing by 38% every seven years (Source)

How it once was – Eugene Gilbert in Bleriot XI attacked by an eagle in 1911

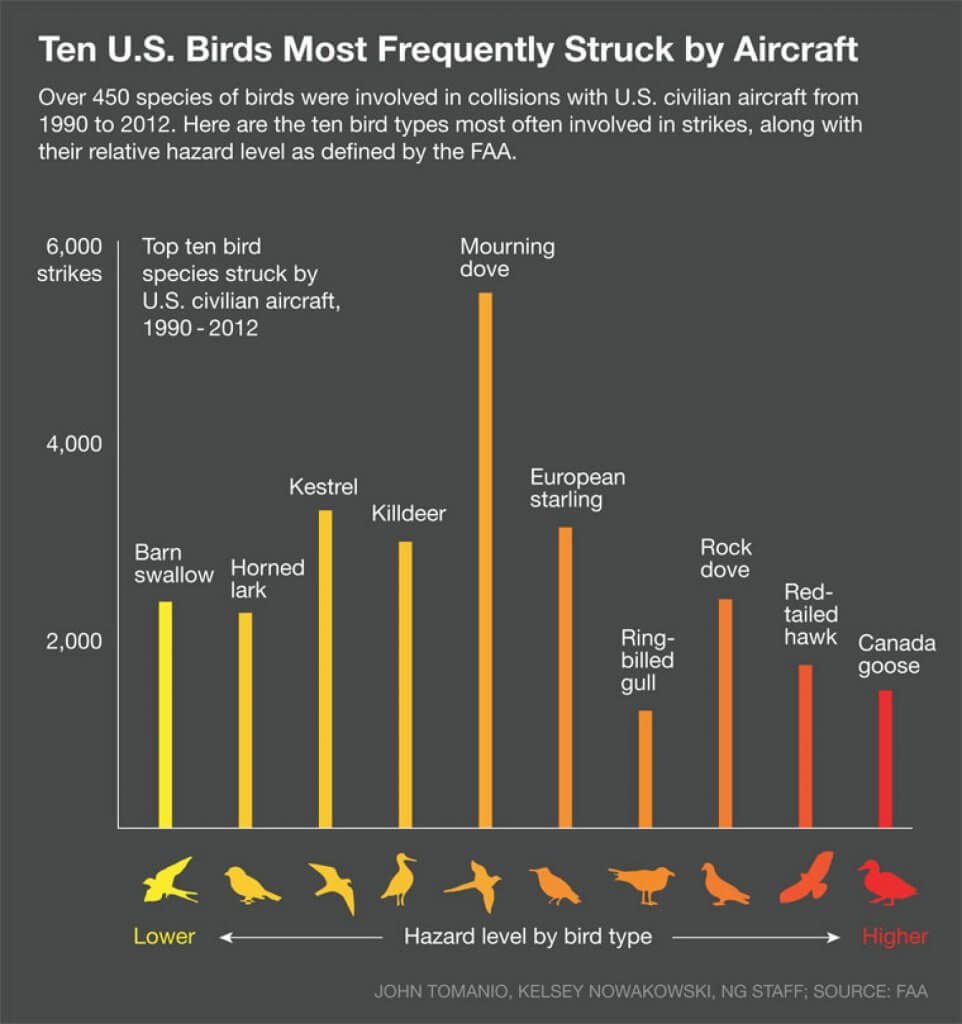

How it is – most common bird strikes in US by recorded species

3 ways to manage bird strike prevention at airports

We looked recently at why the oystercatcher loves airports.

It seems to fly in the face of logic: all that noise and pollution, the sheer number of people and the danger that airports pose should act as a deterrent to birds.

Yet birds like airport habitats for a number of reasons.

- Airports are often found on the fringes of large urban centres, surrounded by large tracts of unused, undeveloped land. This acts as a noise and safety buffer for humans but for birds, it is often the only usable nesting space for miles around.

- The noise and danger of the airport make it an attractive location too. The large metal flying vehicles, the constant human presence, and the incessant noise can actually offer smaller birds something of a sanctuary, as they deter large predators threatening the smaller species.

- Many airports are situated close to substantial wetlands or drainage ponds because the water acts as a sponge soaking up the noise. This makes the area attractive to migratory waterfowl, gulls, and other large birds.

Here are the three main ways to minimise the attractiveness of the airport environment to birds:

- Modifying the habitat

- Controlling bird behaviour

- Adapting flight times and paths

A flock of birds surrounds a plane on take-off

Modifying habitat

Birds can be encouraged to seek alternative nesting and feeding grounds in a number of ways.

These include:

- Removing food sources, such as seed-bearing plants

- Removing food sources for the insects that birds eat

- Covering ponds with netting to prevent birds from landing

- Destroying bushes and trees that offer attractive nesting sites

- Maintaining the necessary grass level required at the airport

Modifying bird behaviour: Bio-acoustic technology and beyond

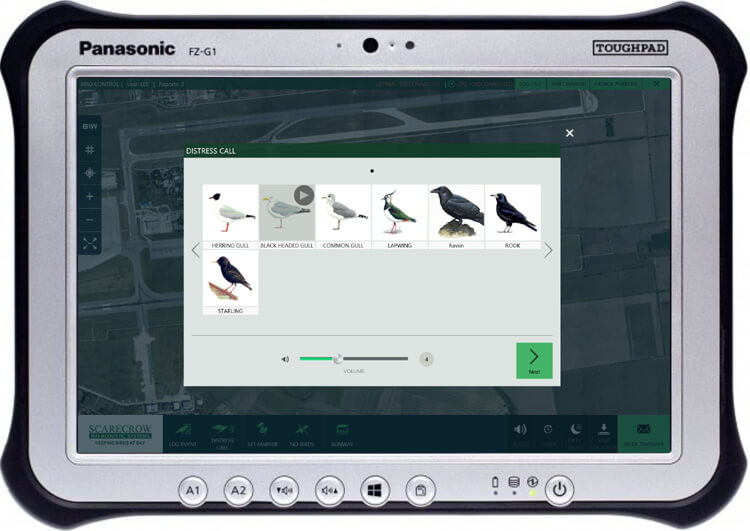

Bio-acoustic technology – the use of specific bird distress calls to disperse birds from airside locations – is hugely effective, but having a full toolkit of bird strike prevention techniques is beneficial to any airport management team.

Other techniques include:

- Using sonic cannons and other unexpected noises to disrupt birds

- Using lasers (at dawn and dusk) to simulate predators

- Flying trained falcons (or drones) over nesting sites to prevent birds from nesting

- Training dogs to track through the airport and surrounding area as a visible threat

- As a last resort, birds may be captured and relocated or, in extreme cases, culled, with authorisation

Scarecrow’s airport bird control products use state of the art bio-acoustic technology for bird dispersal and bird strike prevention

Modifying flight times and paths

Modifying flight paths and schedules can help minimise bird strikes but it is often simply not feasible. There are many other minor tweaks that can be made, though.

These include:

- Using trained spotters to pinpoint the location of hazardous birds and direct planes to alternative runways

- Using radar equipment to track and plot the movement and density of bird flocks – this information can be used to predict their behaviour and deploy control techniques more effectively

- Adjusting flight times to avoid the busiest hours for bird activity, such as early morning and late evening, or to make alterations during seasonal migration periods

Moving towards a greater understanding of bird strikes

As mentioned, although bird strike control programs are working effectively, there is still an increase of bird strike risk due to the sheer amount of airplane travel undertaken. The most effective way to minimise the incidence and impact of bird strikes, for airplanes, travellers and birds, is to understand the environment of each airport in more detail.

- Which species are causing the biggest risk?

- When is the risk greatest

- And why are these birds here?

Closer monitoring, greater understanding and more targeted action is needed to counteract the fact that airports are getting busier, more flights are being scheduled and alternative habitats for birds are shrinking.